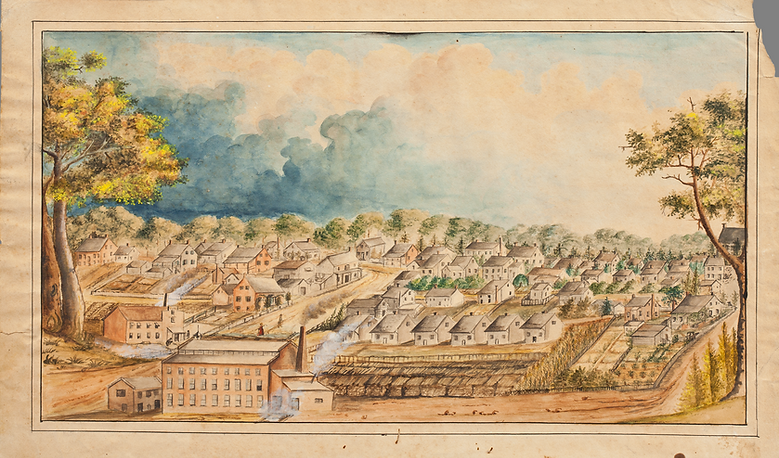

View of Salem from the West

The painting “View of Old Salem from the West” is one of most intriguing and thought-provoking objects that was salvaged from 19th century Salem, North Carolina. Maria Steiner Denke expresses her natural talent and appreciation for art here while also underlining the story of Old Salem’s progression towards an industrial city. Although it contains no words, the painting’s style and artistic devices allow us to take a closer look into the history of Old Salem and the influential impact slavery played in its advancement.

Maria Steiner Denke, the author of “View of old Salem from the West”, was a woman of many talents. She was a fabulous artist, a talented musician, and a passionate educator. Maria grew up a devout Christian and chose to pursue this path by immersing herself into the church and community, always contributing to the wellbeing of those around her (Old Salem Museum & Gardens). Through years of hard work, she made a name for herself among her peers as a teacher at her local boarding school, where she eventually cemented her reputation as a well respected community leader (Old Salem Museum & Gardens). Despite the fact that her name is unknown to many people, her life was full of fascinating stories and impactful contributions that compel immense appreciation from those who study her today.

Although she lived in Old Salem for the majority of her life, Maria was born in 1792 in Bethabara (Old Salem Museum & Gardens). Born into a religious household, Maria was separated from her family at the age of six when her parents, Abraham and Christina Fisher Steiner, left Wachovia to serve as missionaries. She went to live with her aunt and uncle where she became one of the first local girls to attend the Salem Girls’ Boarding school, which opened its gates for the first time in 1804 (Wachovia Database). Along with one other local girl, Maria was admitted strategically in an effort to help assimilate the other enrolled girls to the Moravian community, as most of them were outsiders at that point. This speaks to Maria’s demonstration of leadership and friendliness at an early age. She continued to prove her willingness to lead by joining the staff of her alma mater in 1811, where she went on to teach the young girls of Salem for more than fifty years. During her time at the boarding school, she became a member of the Elders’ Conference and was also appointed the “Pflegerin”, or leader, of the Single Sisters’ Choir in Salem (Wachovia Database). Throughout her life, Maria built upon her religious roots by actively engaging in her faith, dedicating much of her time to service around the Church as well as her community.

Aside from her heavy involvement in the school and the Church, she made time for a pretty comfortable family life. At the age of 36, Maria married a man named Christian Friedrick Denke (Wachovia Database). Maria had no children and continued her work as if she was a single woman. Although she had no children, she treated the young women of Salem as her own. Her educational skills proved very influential on the young children of her town, contributing to the rapid growth and prosperity of the Moravian community and the town of Salem alike.

While she is often recognized as a dutifully minded individual, she was also known to prioritize her own interests and personal satisfaction at times. In 1823, Maria had plans to go on a recreational excursion to Bethlehem with a few other peers of hers within the community. The Elder’s Conference, however, advocated against this trip on the grounds that Maria was responsible for her duties as “Pflegerin” at home. Maria, more willing to give up her leadership position than sacrifice a long-awaited trip to Bethlehem, decided to leave anyway. Interestingly enough, even though she abandoned her office duties in 1823, the records do not indicate her leaving office until 1824 (Wachovia Database). Evidently, this was a tough change for the committee. As further evidence to Maria’s unregimented tendencies, she chose to give music lessons to a young woman outside of the school named “Miss Kerr” (Old Salem Museums & Gardens). This unsettled the church as the leadership had not given her direct permission to do so. Although it may not always have garnered praise at the time, Maria’s passion for teaching and willingness to help others is definitely evident now.

Another momentary initiative that was not necessarily commended at the time was Maria’s interest in African-American education. As one of the founding members of the Women’s Missionary Society, she took pride in being able to introduce religion to Black people and the enslaved population (Old Salem Museum & Gardens). In her memoir, we learn that "a number of years alone, at times assisted by others, she...attended the African Church, and gave religious instruction to such colored people as were willing to avail themselves of the privilege” (Denke, 1808). This active interest in the pursuit of African American religion and education show the true duality of Denke’s character.

As an avid artist, we can assume that Maria indulged in knitting, sketching, painting, and more creative hobbies. There are two main objects that were salvaged from Old Salem that we can confirm were created by Denke herself. The first is the Dresden work sampler created from chained stitch. This is an eye-catching piece of cloth containing various patterns that appear to consist of ovals and curled leaves (OSMG Collection). The other and more popular piece of art created by Denke is the watercolor painting depicting the town of Salem. The piece titled “View of Old Salem from the West” is one of the most fascinating objects discovered from Old Salem, and the driving artifact behind this examination of Denke and the Salem community.

When “View of Salem from the West” was painted, Salem was undergoing a transition from a church-centered, congregational town to an industrialized factory town. At Salem’s founding as a congregational town, the Moravian church controlled nearly every aspect of life, including who was allowed within the town limits and what could be built on each lot (Lewis 2007). By the mid-1850s, the the church’s control over the town had lessened, but its influence remained intact (Lewis 2007). The people living within Salem still touted their religious values as being the cornerstone of their society, even as the town moved into the industrial age.

North Carolina’s access to natural resources, cheap and/or free laborers, and capital made the state a hotbed for new mills and factories (Walbert ). Industrializing Salem would allow for a mass influx of capital to flow into the town, giving its citizens access to growth opportunities and a personal sense of success. In the mid nineteenth century, when “View of Old Salem from the West” was painted and Salem was moving into the industrial age, the notion of manifest destiny was sweeping the entirety of the United States (Reglae 1). Expanding capital, landmass, and achieving a sense of growth was crucial to the American cultural idea of success. This ease in development proved appealing for residents of Salem, but also contradicted the town’s religious roots. In reaction to this contradiction, citizens sought to reconcile their staunch religious beliefs and background with their desire for economic and societal progress. Denke’s work seeks to capture this transition from her individual position; according to Denke, the industrialization of Salem was a symbol of progress that did not interfere with Salem’s moral past.

The style of Denke’s painting, “View of Old Salem from the West'', presents an interesting intersection between the way she frames a narrative around Salem versus the truth of what Old Salem was to other members of that society. Like any historical document, piece of art, or literature, Denke’s painting must be studied and interpreted through the lens of her own bias and position within society. In studying the devices she employed in her “View of Old Salem from the West'', one has the ability to consider the story she intends to tell through her work. This, in turn, allows for an audience to understand Denke’s personal history and understanding of Salem in contrast with those individuals who were not privileged enough to be able to tell their own stories.

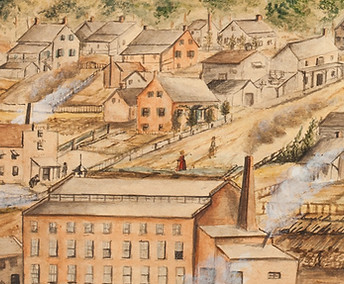

Denke “sets the stage” for the narrative she intends to tell about the history and development of Old Salem through her use of trees surrounding the town. This is defined as the artistic tool “coulisse” which creates a frame around the image itself, much in the way curtains frame a performance (Oxford Art). This feels metaphorical for the way in which an audience may interpret “View Old Salem from the West'' as a whole; the depiction of what an audience sees is merely a performance of the town’s history itself. Coulisse, historically, was used to depict an idealization of pastoral life, which seems to be keeping with Denke’s intention of framing industrialization as complementary to Salem’s congregational past (Larson 376). The painting tells an idealized story of progress, simplicity, and uniformity, but the root of that apparent progress was reliant on the subjugation and dehumanization of enslaved people.

The notion that the industrialization of Salem was the natural path of progress is central to Denke’s depiction of “View of Old Salem from the West''. The directional movement of the painting is a key indicator of this perspective. Denke seems to paint Old Salem with the assumption that the audience would, essentially, “read” this work from left to right. She symbolizes progress through a contrast of coloring in the sky, which moves from dark, stormy, and in high contrast with the rest of the painting, towards a hazier, more uniform coloring on the right side. This indicates that Denke interprets industrialization as a tool of advancement and conformity.

Similarly, the smoke depicted from the mills also moves from left to right. This not only mirrors the sky as a symbol of progress, but also mirrors the shape of the clouds themselves. By comparing the smoke, a product of technology, to the clouds, an inherent aspect of nature, Denke communicates that industrialization works in tandem with and harnesses the power of the natural world. This, in turn, contributes to the message of the painting itself: the development of Salem was not contradictory to the church-centered virtue of its past.

Denke makes references to the ease of transition into industrialization while maintaining Salem’s moral values. The farm on the right side of the painting also depicts this moral value as Christianity supported the transformation of natural lands into inhabitable areas. Agriculture and the cultivation of land has helped spread Christian influence throughout the Western world and was often supported and fueled by Christian missionaries (Kobes, 2016). Therefore it is understandable and presumed that Denke’s inclusion of farmland was to portray Salem as a moral area.

It is possible that Denke was using this painting to create moral justification for the use of slavery. Her depiction of people in the painting can be viewed as proof of Salem's success as an industrial city. The people represent a large and growing population which proves that the shift from congregational to industrial living was successful. This seems to be the center argument of her painting as well as her belief as a Christian woman.

Another important aspect of the painting is the analysis of the buildings. The neat arrangement of houses next to the mill housed Moravian mill workers, who were paid a standing salary. As time went on, the transition to industriailization as well as “the prevailing shortage of labor” (Africa, 276) sadly paved the way for slavery to become more prominent in Salem. The cotton and leather mill owners realized that in the long term, an investment in enslaved people would be cheaper than paying Moravians a salary. Along with the mills, the other houses in the painting seem to blend into the natural background which indicates that Denke may have believed that the buildings belonged where they were in Salem.

Following this theme of progression, it is important to note that although Salem was progressing as a more industrialized city, it was also returning to a previously more barbaric state through the adoptation of slavery. As previously discussed, Salem was a congregational town before industrialization. The town that existed before the painting was extremely focused on and dedicated to religion. According to the Moravian Archives and the History of Old Salem on mywinston-salem.com, the Moravian people that started the settlement were active german-speaking missionaries who came to America to escape religious persecution. The town was built with a “broad main street, narrow side street, narrower side streets, and a central square” (Schenker, 2014). The center square was later moved and surrounded by church buildings including the Single Sisters House where Denke later worked.

From regulating taxes to controlling the price of goods, the church played a heavy role in governing Old Salem. Salem residents even built homes on land leased by the church as they were not allowed to own their own land (Schenker, 2014). As a town, Salem sold many products to nearby areas and became known as a prominent trading hub. As their success in trade grew, the town cleared more trees to create space for new buildings. By the start of the 1800s, individuals were defying church teachings and decreasing the church’s power by owning enslaved individuals (Schenker, 2014). The industrialization of other communities and the popularity of trade products led to the creation of mills as well as the use of enslaved individuals to create a successful economy.

After the production of the painting, the initial town of Salem became a successful city which eventually merged with the city of Winston, which had grown to three times the size of Salem. Overall, “View of Salem from the West” portrays Salem's transition from a struggling trade town to a successful industrial town through the labor of people who were forcibly enslaved.

Salem Moravians had enslaved people up until the Civil War, and as time progressed from the start of the 1800s to 1860s, enslaved individuals were becoming less equal in the eyes of the white Moravians (Negotiated). Before slavery, the Moravian population believed that all Moravians were equal whether white or black (Negotiated). However, as slavery became more common in Salem, white Moravians stopped being buried next to black Moravians and many stopped worshipping together (Negotiated). Enslaved individuals became clear second class citizens by the 1820s and the change that Salem had been undergoing was beginning to become transparent. In an effort to fight this, Women’s groups like the Female Missionary Society and Denke’s Single Sister’s Choir “taught African Americans to read and write even after 1831, when the state of North Carolina made teaching reading and writing to enslaved people illegal”(Negotiated). Although life for enslaved individuals was less harsh in Salem than in other parts of the south, it was by no means an easy life. The enslaved built the structures, the furniture, and practically everything else with functionality in Old Salem yet received no credit and only punishment for their work.

Denke’s ability to portray Salem from her personalized lens was uncommon for the majority of citizens. Denke was a woman of privilege for her time; she received enough education to lead organizations like the Single Sisters, educate members of the African American community, and paint well enough to create a studied historical document (MESDA). It is safe to say that the story she sought to capture in her painting did not mirror the experience of other citizens of the town. In “View of Old Salem from the West”, the perspective of the painter seems to be outside of the town itself, giving Denke the ability to frame a narrative of Salem that she believed to be true. The vast majority of Salem residents, and more specifically Salem's enslaved population, never had the opportunity to tell their own stories and depict Old Salem through their own experiences.

The historical truth of Salem lays at the seams between the stories and myths that are told about its development and the truth of the lives that were stolen there. It is true that industrialization in Salem led to the vast development of its economy, but it is also true that this financial boom was at the expense of enslaved people. It is largely recorded and understood that Salem’s transition into the industrial age was a moment of progress for the town, but that myth lacks context, and is not the whole truth for many citizens residing in Salem. Although the story that Denke tells in her painting is the truth, it is only her truth. “View of Old Salem from the West'' seeks to capture the story of Salem as a whole, but in reality, it only seems to capture Denke’s individual experience and viewpoint related to the town.

Most knowledge of American history mirrors the story told in Denke’s painting. Historians and authors are often quick to acknowledge the progress the United States has made without recognizing the price of that progress. When studying monumental moments in American history, emphasis is placed on a continued story of improvement, rather than crucial points of abuse, erasure, and continued subjugation. This narrative of progress may stem from the fact that the documents recorded and studied are written, painted, or made by those whose lives were improving; Denke’s depiction of Salem’s progress may have felt true due to the nature of her life, but it did not necessarily mirror the lives of everyone living in Salem during this time period. The voices that are recorded and taken as fact throughout history come from a place of significant privilege. After all, history is written by the victors. Without recognizing the implicit bias of our historical documents, one’s understanding of the development of the United States is bound to be skewed and incomplete.

While it is important to take all factors into account when reviewing our nation’s past, there is still much to be learned about American history when studying biased artifacts such as Denke’s “View of Salem from the West''. It is impossible for history to be recorded through an unbiased lens, and thus a historian must take the time to understand the context of an entire moment before dissecting one interpretation of it. Denke’s “View of Old Salem from the West'' feels like a justification for industrial progress, and, more importantly, the use of enslaved people as a means to that end. The institution of slavery and the continued subjugation of Black bodies has always been for the sake of White “progress” and advancement of an unjust society. The common perception of slavery and the caste system born from this American institution is that it stems from mass ignorance or hate. As seen through Denke’s work, the privileged American population was not necessarily hateful or ignorant (although hatefulness and ignorance were surely born from these systems), but rather it was willing and able to subject others to a life of suffering in order to achieve what it believed was a greater good for society. In reality though, these were just self-serving goals that only benefited a fraction of the population.

Studying American history does not reside in what decisions were made, but rather why people chose to make them. “View of Old Salem for the West'' gives insight into why citizens of Salem utilized slave labor for mills and factories through the use of pointed artistic devices. Denke uses the image to frame industrialization as a powerful tool for morality and economic progress, mirroring the general perception of industrialization held by many people at the time. The institution of slavery and usage of slave labor within these mills were not even alluded to in her work, despite her work in educating Black individuals. This can give one an understanding that the loss of livelihood for Black individuals was so necessary for Denke’s understanding of progress that enslaved people were not even worth mentioning.

“View of Old Salem from the West'' does not provide an accurate depiction of Salem, but it does allow modern historians, teachers, students, and all others a window into the societal goals of Salem and the story it wished to tell about itself. Denke’s use of artistic elements mirrors the way writers employ literary devices; her art was made with a goal in mind and an opinion to communicate. We do not have access to a visual representation of Salem from a Black citizen living at the time given that they were not allowed the leisure time or education to create art and tell stories unless it served a functional purpose. Thus, their depiction of the same Salem would likely feel different, and communicate a different opinion and goal. With vastly different circumstances that existed for different identities, the setting and story of Salem is subjective. The bias in this painting, however, should not deter anybody from recognizing the beauty it has to offer. It should rather encourage people to imagine how Salem would look on the other side of history. If given the opportunity, would African Americans portray Old Salem in a similar light or would they be more compelled to highlight the prejudice rooted in its advancement?

Object biography by Roddy Crawford, Maggie Hutchins, Sarah Sanda, Samuel Walker. Spring 2021

Denke's home with her husband Christian

Denke's sampler

Interpreting Denke's Painting:

Expanding capital, landmass, and achieving a sense of growth was crucial to the American cultural idea of success. This ease in development proved appealing for residents of Salem, but also contradicted the town’s religious roots. In reaction to this contradiction, citizens sought to reconcile their staunch religious beliefs and background with their desire for economic and societal progress. Denke’s work seeks to capture this transition from her individual position; according to Denke, the industrialization of Salem was a symbol of progress that did not interfere with Salem’s moral past.

Coulisse

creates a frame around the image itself, much in the way curtains frame a performance

“Overall, “View of Salem from the West” portrays Salem's transition from a struggling trade town to a successful industrial town through the labor of people who were forcibly enslaved.”

“The vast majority of Salem residents, and more specifically Salem's enslaved population, never had the opportunity to tell their own stories and depict Old Salem through their own experiences. ”

Works Cited

Africa, Philip. “Slaveholding in the Salem Community, 1771-1851.” The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 54, no. 3, 1977, pp. 271–307. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23529858. Accessed 8 May 2021.

“Denke, Maria Steiner, Old Salem Museums & Gardens, https://www.oldsalem.org/item/collections/view-of-salem-from-the-west/10409/

“Dresden-Work Sampler.” Mesda, mesda.org/item/collections/dresden-work-sampler/6724/.

Kobes, Wayne. “Reclaiming a Biblical View for Agriculture.” In All Things, 29 Feb. 2016, inallthings.org/reclaiming-a-biblical-view-for-agriculture/.

Larson, James L. “The Four Pastoral Epistles.” Scandinavian Studies, vol. 44, no. 3, 1972, pp. 392–409. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40917411. Accessed 8 May 2021.

Lewis, J.D. Salem, North Carolina, www.carolana.com/NC/Towns/Salem_NC.html.

“Moravian Archives, Winston-Salem, NC.” Moravian Archives WinstonSalem NC, moravianarchives.org/.

Memoir of the Widowed Sister, Mary Denke, November 27, 1808

“Nineteenth-Century North Carolina Timeline.” Nineteenth-Century North Carolina Timeline | NC Museum of History, www.ncmuseumofhistory.org/learning/educators/timelines/nineteenth-century-north-carolina-timeline.

“Old Salem Inc.” Facebook, www.facebook.com/OldSalemInc/posts/10157804799995009/.

Regele, Lindsay Schakenbach. “Industrial Manifest Destiny: American Firearms Manufacturing and Antebellum Expansion.” Business History Review, vol. 92, no. 1, 2018, pp. 57–83., doi:10.1017/S000768051800034X.

Schenker, Alex, et al. “History Of Old Salem.” MyWinston, 19 Nov. 2014, www.mywinston-salem.com/history-of-old-salem/.

Schumacher, Jessica Robins, "Common ground, diverging paths: eighteenth-century English and French landscape painting." (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3111. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/3111

Walbert, David. “NCpedia: NCpedia.” Link to NCpedia Main Page, www.ncpedia.org/anchor/industrialization-north. “Negotiated Segregation in Salem.” www.ncpedia.org/anchor/negotiated-segregation-salem.